When I began the genealogical research into my diverse family, I had no idea that it would challenge how I viewed myself and perhaps even my sense of identity. The journey began around 2007 when my parents visited me in Montreal and shared a copy of the Hart family tree that was given to my dad by his cousin, Ian Hart. Since childhood I had always heard that we were related to the Hart family who lived two doors down from us on Chacon Street, San Fernando, and that my paternal grandmother’s father was a Hart… I do not think I even knew his full name then. Curiously, when my family moved to Palmiste Estate a few years later, I discovered that our new neighbours two doors over, the Lynch family, were also related to us via Hart. I guess I took in this new information at face value and beyond the initial curiosity, my relationship with them developed more into close friendships than family connections. Nonetheless, in Trinidad culture, every adult connected in any way to our parents is either Uncle or Aunty. Thus, Uncle Rolf and Aunty Marilyn became role models and confidantes like others among my uncles and aunts.

Discovering the family tree though was not a curiosity, but a shock. Family ties to other people I either knew or knew of were popping out all over the document pages. The names of persons about whom I never imagined any family connection suddenly took on meaning that would probably have changed our relationships. Hmmm! … Aunty Janet S is Uncle Ian H’s sister? … X on whom I had an adolescent crush is now related to me? What a hoot! … Also Y and Z, previous college classmates, are my cousins… distant nonetheless?

I launched headfirst into this adventure, first by manually entering all the Hart family’s data into a genealogy program on my Mac. Then, seven years later, during my sabbatical year, I started actively building an online family tree on Ancestry and began researching the other branches of my family. I founded two Facebook Messenger groups to connect with family members and share information on both sides of my family. I also co-moderate the Hill Family Tree Facebook group with my cousin, Kimberly. Thus, I have been able to reunite with lesser-known family members, many of them from across the planet.

My paternal great-grandfather, Henry Eric Hart (1872-1950), had a daughter, Nasaria Alexandria Lopez (1906-1953), my grandmother, with Christina Constancia Lopez (1888-1960). He is the grandson of Daniel Hart (1806-1869) and the seventh of ten children of Michael Albert Hart (1834-1906) and Maria Emilia Felicia Gomez (1839-1913). Henry trained and raced horses in Arima, Trinidad. He also fathered nine other children from different marriages. The Harts were prolific progenitors and the family lineage today seems to be everywhere in Trinidad and elsewhere.

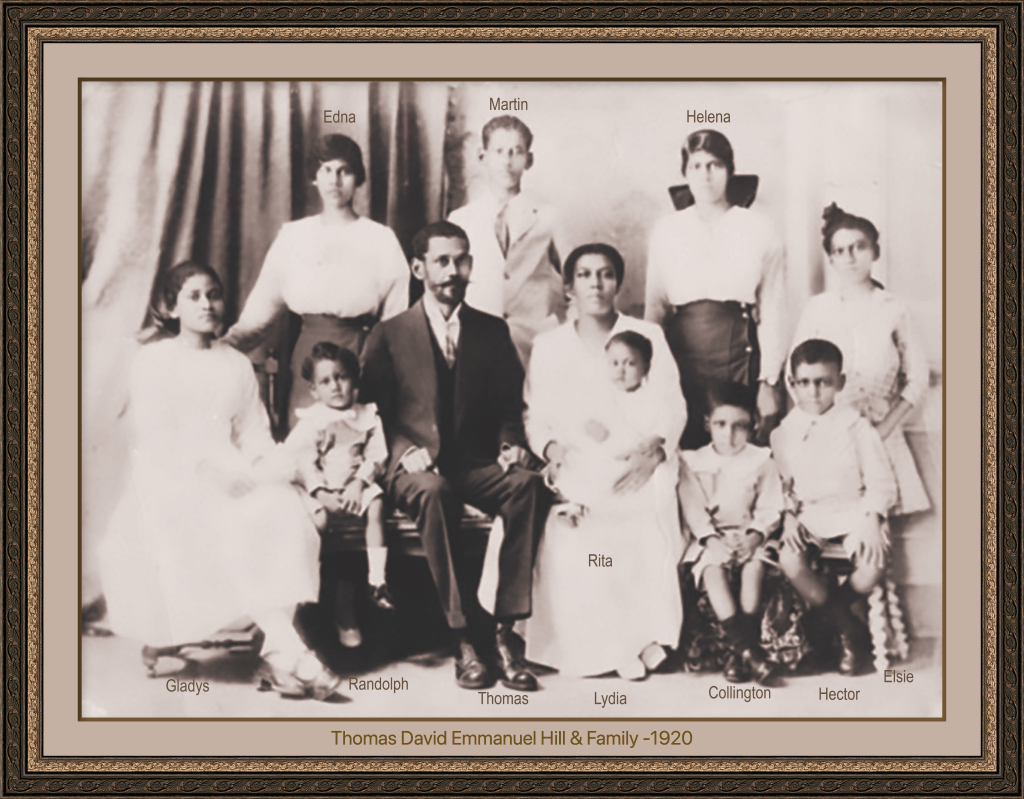

My other great-grandfather, Thomas David Emmanuel Hill (1872-1960) was born in British Guiana. He married Florence Pryor who gave him four children, but she died in the childbirth of my maternal grandfather, Martin Welles Hill (1906-1989). Thomas then moved to Trinidad with his children. He remarried with Lydia Caroline Gibson and fathered ten children with her… the last, being my great-aunt, Jean, who was born in New York in 1927 when Thomas and Lydia lived there.

Aunty Jean is a year younger than my mother and after Lydia returned to Trinidad with her in 1930, she and Mom ended up in same class at school. She was the last survivor among his children for many years and died recently in Boston on the 21st of October 2021, a month before her 94th birthday. She leaves four surviving children; Judith and Jonathan Herbert, Leah Hill and Ian Sue Wing, and her two grandsons Francis Hill and Andrew Wood-Sue Wing.

You will always be remembered, Aunty Jean,

and may you Rest In Peace.

Thomas also had a daughter, Hortense Watson, in Guyana before his first marriage. Recently, though, through a strong DNA match to me on Ancestry, I discovered Linda, another cousin from South Carolina, whose mother, Maude, was born in New York to Thomas and Helen Amoroso the very same year as Aunty Jean. Lydia returned to Trinidad in 1930 with Jean who grew up with my mom, her niece. Around the same time, Thomas left New York for London where he stayed during the war years and eventually returned in 1959 to Trinidad where he died soon after. I vaguely remember him sitting in the gallery at my grandparents’ home. He was quite sick and was being cared for by my grandmother, Mary, his daughter-in-law. I was about five years old at the time and did not understand the nature of his relationship to me. I do not remember communicating with him even though I spent two weeks there. He must have died soon after that, because I never saw him again.

Thomas and Lydia’s children mostly migrated to the US and some had successful careers in the military and/or in the arts. The eldest son, Hector, moved up the ranks of the military and was also a musician. His grandson, Theo Hill, a very accomplished Jazz pianist, was famously accompanied by Bill Clinton on the saxophone on Martha’s Vineyard.

There was also Collington Carl Gibson Hill, who started gaining recognition for his watercolour artwork in New York, before World War II brought his career to a tragic end. He was an objector of conscience, but was forced to enlist in the Merchant Navy. He went down with the USAT Dorchester, torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of Newfoundland on February 3, 1943.

The most noteworthy, though, was their younger brother, Errol Gaston Hill, whose extensive and accomplished international career in the theatre as a performer, playwright, writer and historian made him a recognized authority on Afro-American and Caribbean theatre history. He taught at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire from 1968 to 1989. Among his published works are the plays Man Better Man (1964), Dance Bongo (1966), and Strictly Matrimony (1971). Among his books are The Trinidad Carnival: Mandate for a National Theatre (1972) and The Theater of Black Americans(1980).

My grandfather, Martin, stayed in Trinidad and married Maria “Mary” Presentacion Rojas (1898-1982), my grandmother. They had five children: three boys and two girls. Granddad was also an artist and it was he who gave me my first set of gouache paints and sparked in me an early interest in art. My mom, who is also very creative, noted my interest and sent me for weekend art classes in the early 60s with Hettie Mejias (now Mejias-de Gannes). In the years before leaving for Canada to study Fine Arts, I often visited my granddad in Port of Spain and took pleasure in viewing his work.

I knew very little about my paternal grandfather, 刘树 Lue Shue, who travelled to Trinidad from Guangdong Province, China at the turn of the last century. He took the name Randolph. I never knew him because he died the year before my birth. He married my grandmother, Nasaria, and they had eight children. I was told that he left a wife and children behind in China and I knew that he sent my uncle Kui Loy, his first Trinidadian-born son, to China to learn Chinese. However, I was surprised to discover from some newly discovered travel documents that my uncle was only ten years old when he left for China in 1934. He travelled then with Nathaniel Lue Keow and his daughter Vera Ayin. He spent four years there before returning to Trinidad. I also discovered, written on his return travel documents, the name of my Chinese-born uncle, Lue Tin Fook, as well as the name of the ancestral village, LiLong. I also found in my research via a recent obituary in a Trinidad newspaper that he had a daughter, Beulah, from an earlier relationship in Trinidad. We have since met and welcomed her children into the family.

Researching my Chinese heritage has been difficult, mainly because I had so little information initially, but also because I do not speak Chinese and did not really understand the historical context of Chinese immigration of the time, nor the cultural customs such as clan names, generational names, school names, names of married women, etc. I spent hours plodding through thousands of names in the ship manifests of Chinese immigrants looking for any clues about my grandfather’s journey to Trinidad. So far, I have found relatively little.

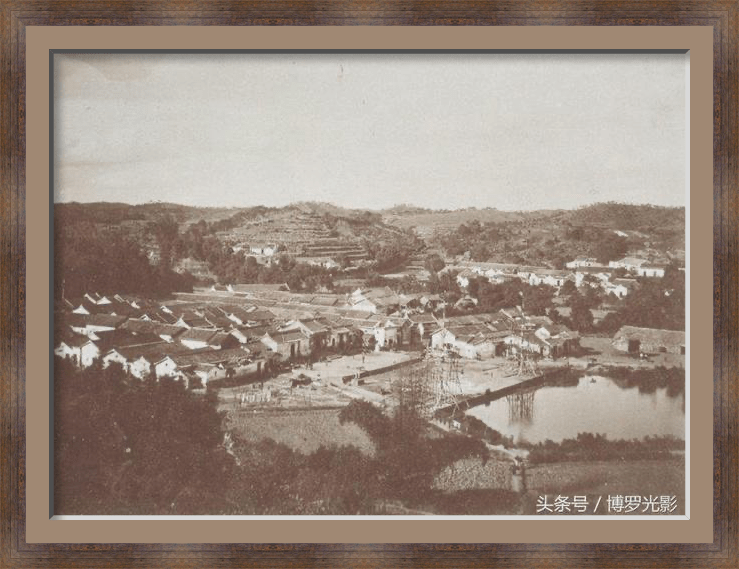

However, I was lucky to find information about the ancestral village, LiLong, which no longer exists as such, as it was bombed twice during World War II. The area is now a part of Shenzhen City, but the old village was the site of the Basel Mission Christian seminary after 1856. It was the first Christian seminary on mainland China. I discovered the online Basel Mission Archives with many photos and documents of that period.

I also figured out how to use Google Translate to effectuate a search in Chinese and then translate the results back to English. I devoured the information that I found about the life and times in the region of Guangdong Province and on the Hakka culture from the districts of Fui Yeung (HuiYang), Bao’On (Sun On or Xin’An) and Toong Koon (Tung Kun) which gave the name of Fui Toong On to a Chinese Association in Trinidad of which Lue Shue, my grandfather, was a founding member.

Unfortunately, I could not share this information with my dad since he was already by then in the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Dad eventually died at age ninety-two, in Trinidad, on the 26th of January 2020, just before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Since then, I have had many strokes of luck in my research, almost as if Dad was guiding me. First, knowing about my research, my sister, Deborah, shared a letter with me that she found among Dad’s belongings; it was dated 2008 and was from his longtime school friend, Father Kelvin Tam, a Catholic priest, now stationed in Cali, Colombia. The letter explained to Dad how the Lue families in Trinidad (Liu 刘 in Mandarin) were all related and were all descendants of the fourteen sons (branches) of Liu Guang Chuan Gong, considered the “father” of the Liu genealogy in Guangdong Province. I also learnt from the letter that Fr. Tam’s mother was a Lue. I immediately seized on his email address in the letter and contacted him. To my surprise, Fr. Tam is still alive and in full possession of his mental faculties. We have been corresponding fairly often since. I am also in communication with other members of his family via Facebook.

I started to uncover other similar stories on Chinese immigration to Jamaica, Guyana, Cuba, Panama, Canada and the Americas, including Hawaii. The administration at the Chinese Benevolent Association of Jamaica has been very helpful and their website has a lot of information, maps and an index of ancestral villages. I attended online conferences and webinars offered by the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles and have made contact on online forums with other Chinese persons researching their ancestral roots. I joined My China Roots and recently attended the 2021 Toronto Hakka Conference which was presented online because of the pandemic. I have also initiated the process to become a member of the Trinidad and Toronto branches of the Fui Toong On Association.

Luo Shui Hap , Longgang, Guangdong

One particular custom I learnt about from the research into my Chinese heritage that I have now incorporated into my life is the honour and reverence shown to ancestors. The traditional Hakka rituals associated with this custom were pejoratively called Ancestor Worship, considered diabolic and were discouraged in the mid-1800s by the growing influence of the Christian churches in Guangdong Province. Without delving into the merits or faults of these rituals, I can say that I do not see much difference from the Christian traditions of cleaning grave sites on All Souls Day and adorning them with flowers and candles. I remember my dad always threw a shot of alcohol on the floor whenever he opened a new bottle of rum or whisky; he said it was for his father. Today, I now name and salute my known ancestors at the start of my daily meditations and prayers. I invoke their presence and invite them to sit with me… I can say that I do often feel their vibrational presence. I also ask them to help me create zones of protection and wellbeing around me, my extended family, my friends and neighbours, all of whom I name individually. Through this ritual, I have the impression of reuniting the past and the present and infusing the future with hope and confidence.

My research has allowed me to appreciate the historical, cultural and social contexts that underlay the decisions made by my ancestors and the outcomes that played out in their lives. I have learnt to suspend value judgments on their choices and to recognize how deeply the legacy left by their passage on this planet are imprinted in my own DNA. I am who I am, here and now, partly because of those choices they made and my life is enriched by the gratitude that I feel for their sacrifices. I realise that the meaning of our lives become more profound when we recognize the spiritual continuity that their lives have imprinted on each of us and which we in turn pass on to our heirs. Our choices make our legacy and it is our responsibility to assure that the baton is relayed smoothly to the next generation.

I understand that family is everything and we are all part of one big human family. We are not only connected in space and time via spiritual and emotional dimensions, but also on the molecular quantum level. For example, I recognize that I presently live on Mohawk ancestral territory and that part of my own Indigenous roots from Guyana, Venezuela and Trinidad is also linked to their ancestral path. I now see why Destiny brought me to Montreal rather than to Paris or London which were my original choices of cities to pursue my university studies. To think that I danced proudly at a Pow Wow at Kahnawake in the early days of my arrival in Montreal without knowing then that my DNA was already connected to the region. Genetic analysis of my patrilineal and matrilineal haplogroups shows that the Mohawk and I share common ancestors. My conscience glistens with warm gratitude and a deep feeling of belonging to the lands and to the peoples with whom I am now connected. That I have long considered myself a Citizen of the World can no longer be considered a personality quirk nor is it a mystery; it is very real for me. My DNA evolved out of four continents and from multiple expressions within four major ethnic groups: European, African, Asian and Native American. I also recognize four religious influences in my own spiritual inclinations: Christian, Jewish, Buddhist and Indigenous traditions.

The Earth is my body; Water, my blood; Air, my breath; and Fire, my spirit.

I can often see reflections of myself in the faces of people from other ethnicities and the reverse has also been true. I know this because my appearance has occasionally aroused some curiosity on the street and I have also been mistaken for other nationalities and addressed in other languages, usually in Spanish, Portuguese or Arabic.

Family is everything and we are one big human family.

In loving memory of my dad and all of my other ancestors.

Andrew

August 2021